In 19th century’s end arose the first echoes of concern by the increasing stress and pressure imposed on those who live in big cities, by the hand of essayists, precursors in a kind of writing that, especially in the United States, was taking its first steps.

Many of those early writings are produced in wild nature to where authors go and isolate themselves in wilderness areas. There they record the experiences, feelings and challenges of prolonged contact with wildlife. The book “Walden” (1854), by Henry D. Thoreau, is a reference in the transmission of this experience.

John Muir, one of the precursors in the creation of the first US national parks and founder of the conservation organization Sierra Club, published “My First Summer in the Sierra” in 1911.

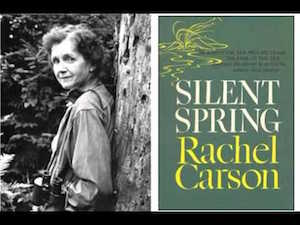

A few decades later, with “Silent Spring”, Rachel Carlson contributes to the birth of the environmental movement in the mid-twentieth century.

Around the same time Edward Albey writes “Desert Solitaire”, an autobiographical work due to the complete season he lived isolated in remote Wild West. Pete Froman was awarded for his work “Indians Creek” published in the nineties. He recounts his experience in the seven winter months spent in the Rocky Mountains.

These works about the need to preserve a world from which man begins to pull away, gave rise to what today is called nature writing, a writing – initially nonfiction – in which nature and wildlife are protagonists.

The worsening of environmental problems and the growing discussion generated around them, motivate an expansion and diversification of nature writing. Besides reports of experiences lived by the authors and the dissemination of increasing warnings by elements of society from various quarters, all concerned with environmental degradation and the resulting loss of quality of life, works of writers and journalists also motivated by this global issue start to appear. This leads them to follow the actions of those that on the ground seek a world that can no longer enjoy the comfort zone where they were born or where they live.

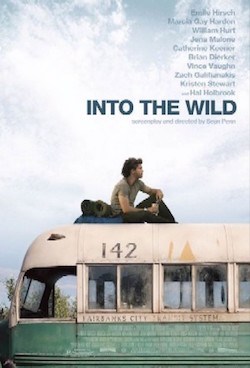

In some cases experiences brought to the limit come to light. As W. L. Ruscho did in “A Vagabond for Beauty” (1973) where, making use of notes from his diary, reports the disappearance of young Everett Ruess that in 1934 plunged into the remote American Southwest Canyon lands to live an experience without return. Jon Krakauer also testified in detail the escape of the current world by Christopher McCandless in Alaska where he found death in the depths of isolation. This was an experience that has acquired a universal dimension with the film version “Into the Wild” in 2007.

Novels also fit in nature writing, a genre that gradually gained importance in the area of fiction. And if some former works were not initially motivated by the theme of nature conservation, this message has become central in the unfolding of each new plot. “Moby Dick” (1851) by Herman Melville, is a must read book for those who look for good literature and action in the wilderness. Recently a new film version was produced. Jack London left numerous publications in a genre in which he was precursor.

There are also works with fictionalized plot where good savages are central characters. One of the most recent is “The Wolf Border” (2016) by Sarah Hall, where the concepts of wilderness and savagery, also human, are confronted.

Inspired by the homonymous work of Michael Punke, “The Revenant” is another recent film. And if the central theme of the story is not so much wildlife but the man’s behaviour, it is the wild nature and the idea of the Border transposition that separates it from the “civilized world” in which we live in that overstates both works.

Travels and remote expeditions, works in the confines of the world are also areas where nature writing always became evident. One of the first editions in this field was “The Voyage of The Beagle”, essentially notes of a diary written by Charles Darwin in the late nineteenth century.

In more recent times, in “The Snow Leopard” (1978), Peter Matthiessen gives us account of the two months of field he spent in the Tibetan Plateau with the naturalist George Schaller in pursuit of that mythical animal of the Himalayas, the stealthy snow leopard.