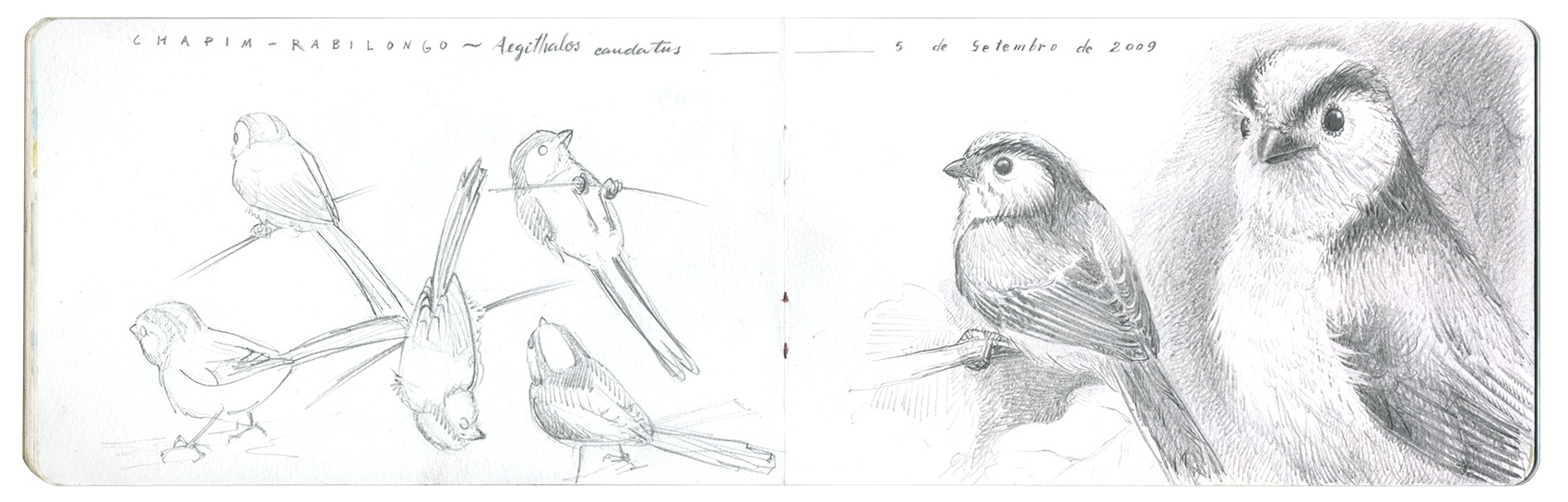

Drawing birds can be a challenge for anyone. Even for the experts. Birds can be very fast. In fact, we hardly have enough time to draw them in a realistic way while they are standing still. That’s why we asked nature Portuguese artist Marco Nunes Correia help. He’s going to lead the way, step by step.

It’s always good to try drawing birds in nature. But it’s very likely that we don’t make it. Even so there are some tricks.

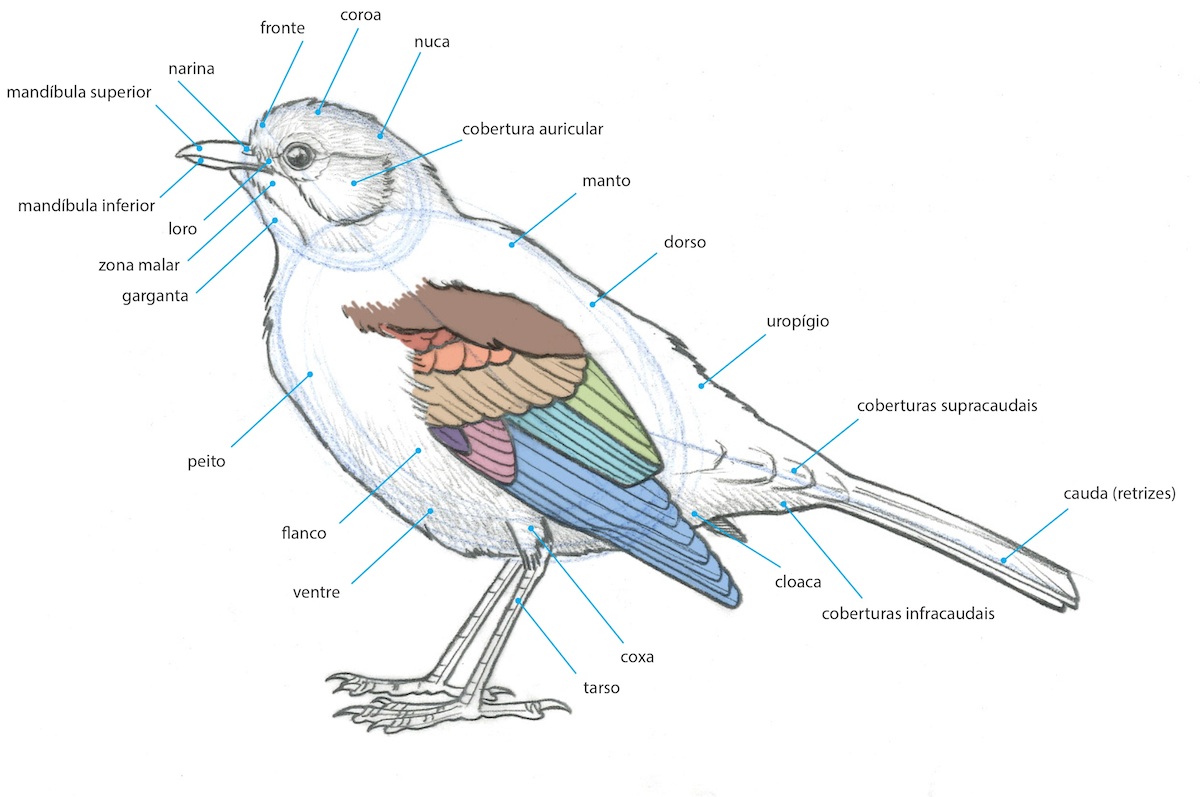

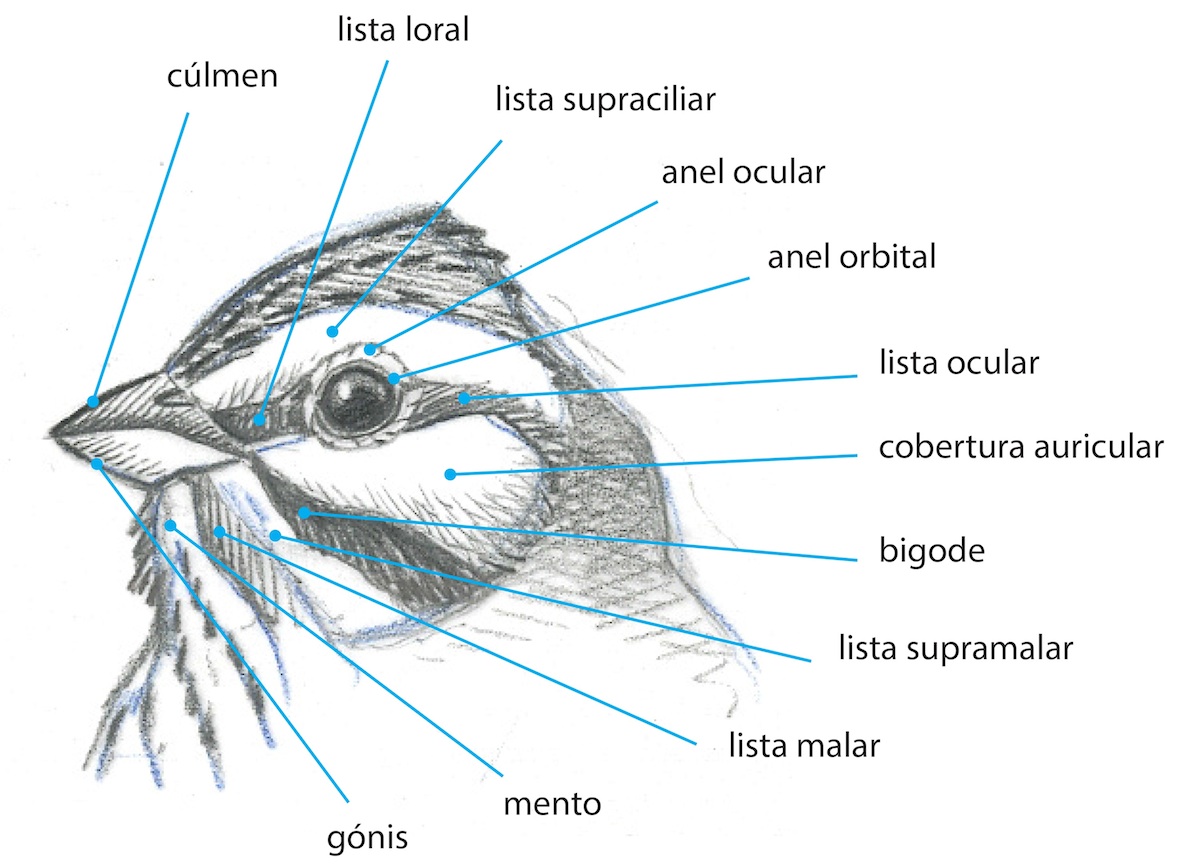

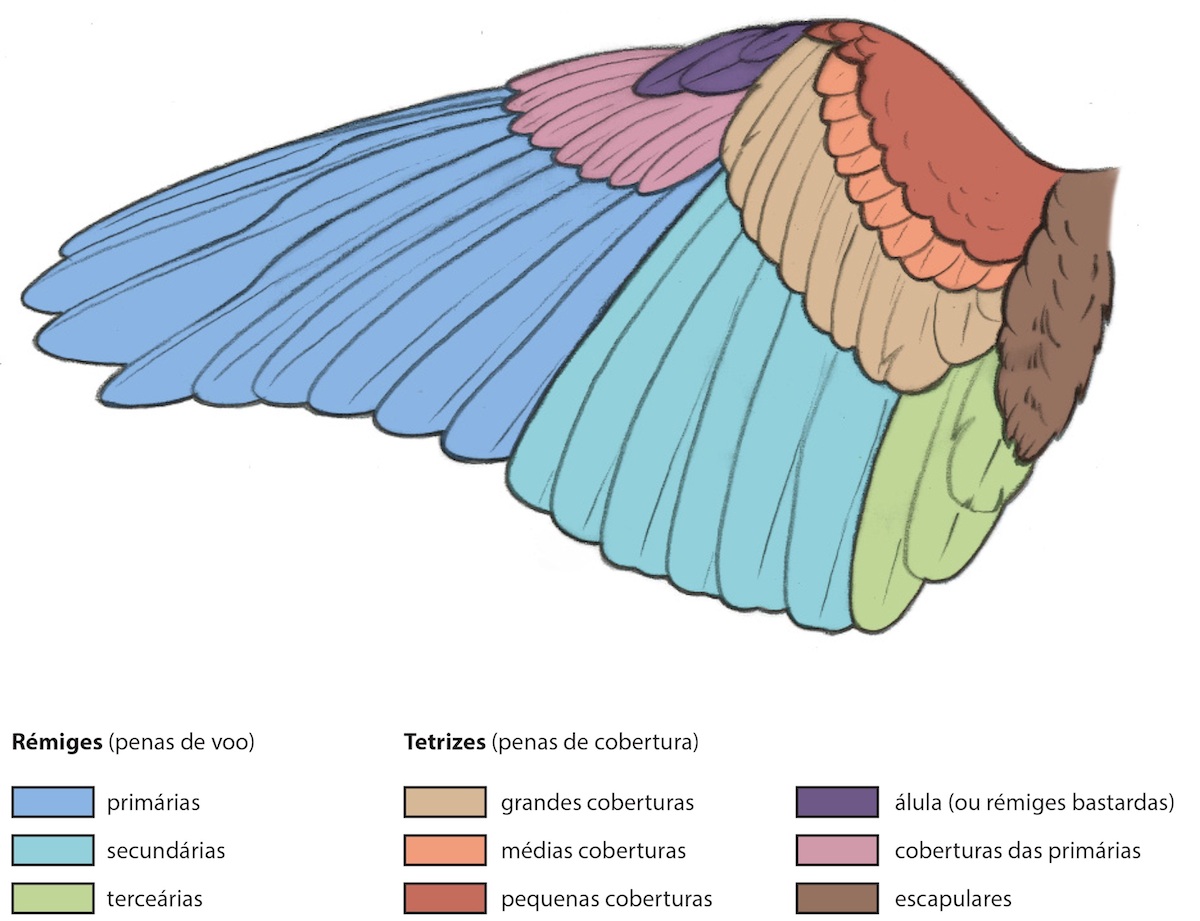

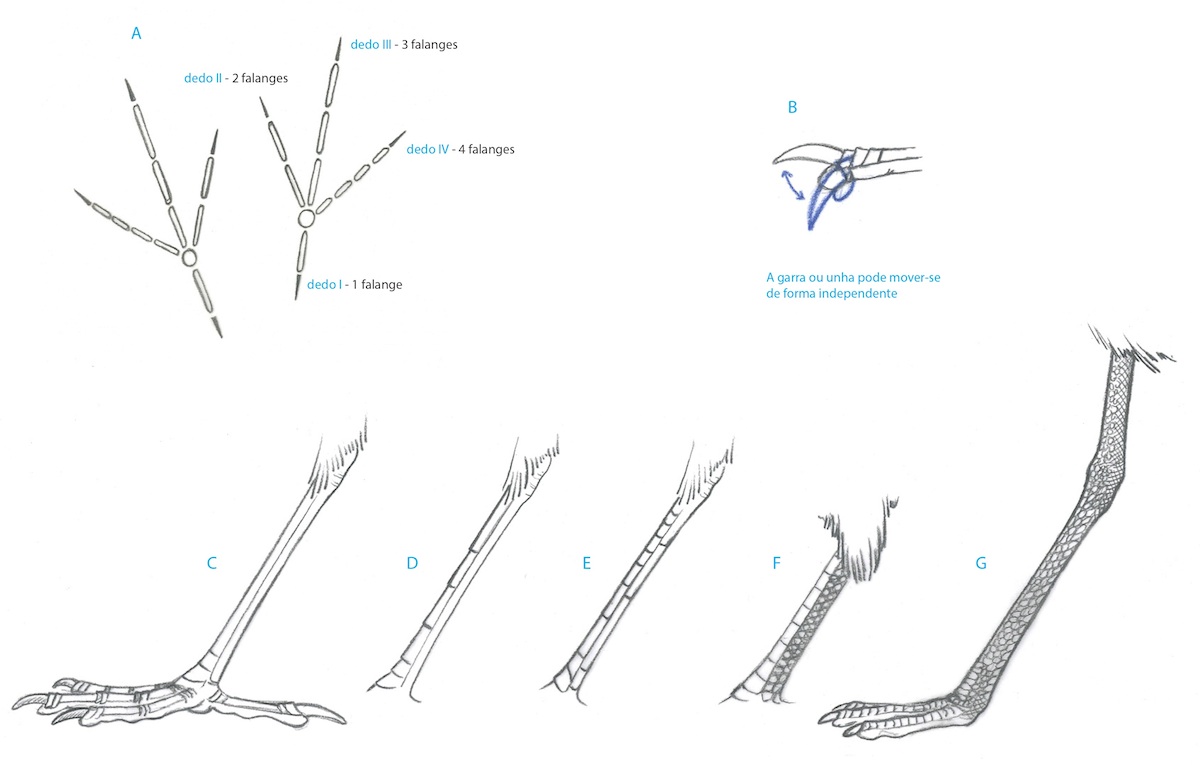

First of all we should learn a little about bird’s anatomy, namely the different groups of feathers, the position of head and paws and the shape of the body parts.

Head, wings and paws are the most complicated parts to draw, even if our model of reference is standing still, in nature, in a photograph or if our model is a taxidermized one. The next images will help you get familiar with bird’s anatomy.

For a better understanding of birds we should study them before going out to draw, even if we can’t learn all the information at once. Knowing the several taxonomic groups is a slow process that requires years of practice. But we have to start somewhere, right?

It’s not enough to go out and start drawing birds if we don’t have a basic knowledge. Studying birds by the books and photographs it’s not enough either. We need many hours of observation in nature, paying special attention to their behaviors, trying to link those to what may have triggered them.

Other crucial aspect to consider is the jizz concept, in other words the attitudes, poses and movements of each species. And this is the most difficult aspect to achieve, be it in our homes or in the field.

Let’s look at some tricks to get us started.

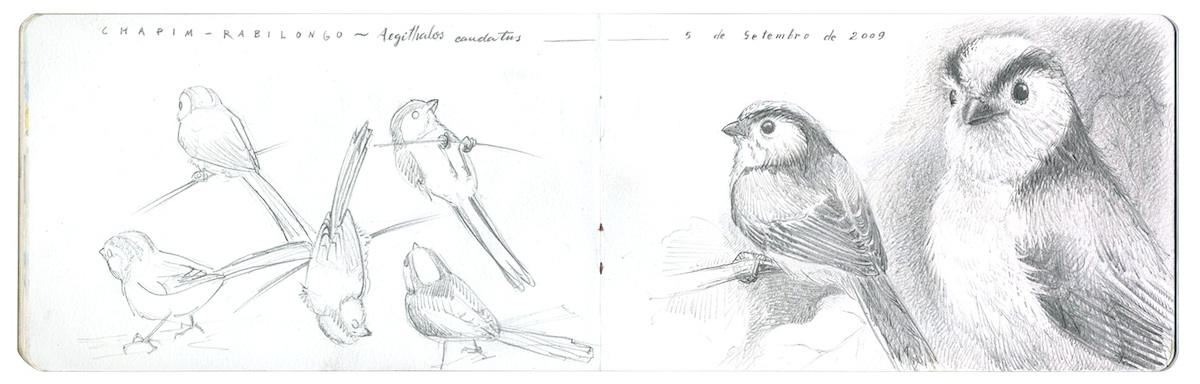

Begin by drawing birds that are standing still, resting or singing on a perch. Usually we tend to draw even what we don’t see clearly, just because we know it by heart. The best thing to do… is not to do it at all. Try to draw only what you are seeing. Use binoculars or telescopes to help you observe birds with more detail. It’s possible that, even so, we can’t see all the scales in their paws or all the claws. In that case, choose not to draw them and make just a little sketch!

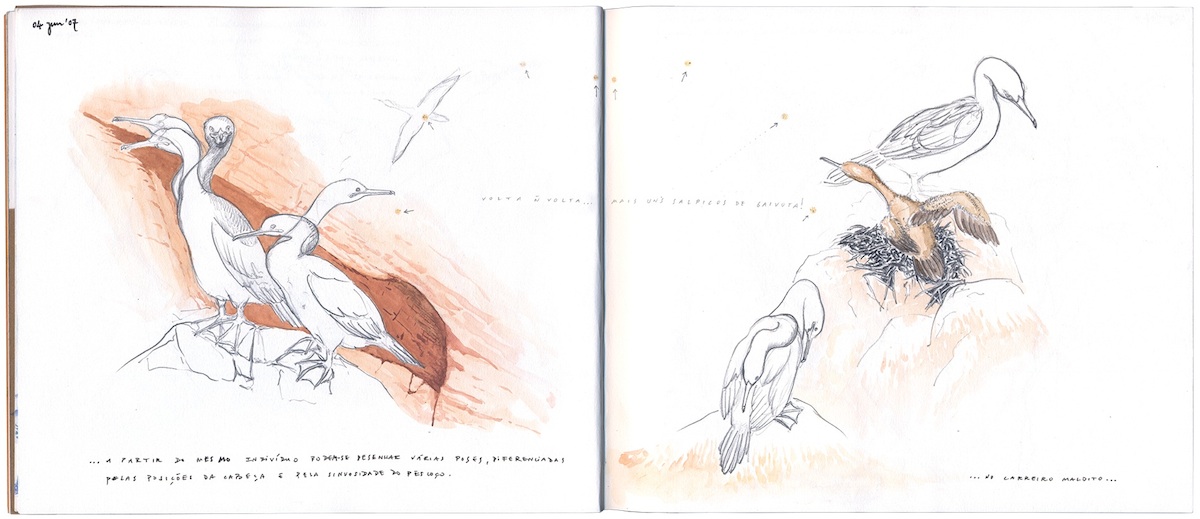

After some time, try to draw birds resting, for instance waders in wetlands. Seagulls, egrets, storks and cormorants are good options too. When birds are feeding, it’s common for them to move just the head. Start by drawing the birds’ body and then several head positions.

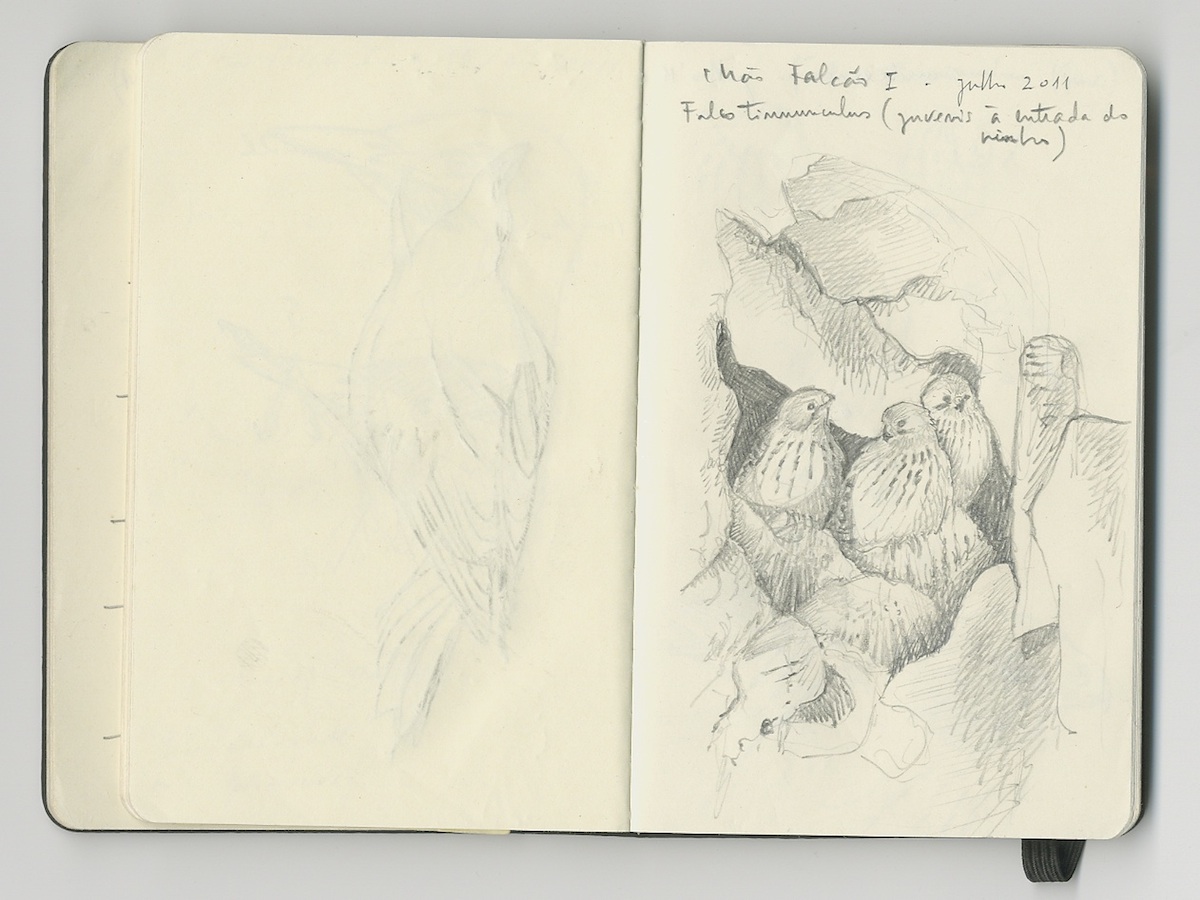

Other technique is to draw sketches of the same bird scattered in the page of your field notebook that you can complete simultaneously, as the bird moves from one position to another. In fact, you can be working on three or five different drawings at the same time. This requires much more concentration, though.

And when you feel more at ease with the birds, you can practice your short-term memory. Take some time to observe carefully the flight of a bird. After that, look down to your field notebook and draw what you’ve seen.

At the beginning this can be a little frustrating because the image that we memorized is deleted from our memory the minute we start drawing. It’s our brain trying to fool us! It’s just a matter of practice. In time we will be gathering knowledge about several species and it will be easier to maintain that memory for a longer time.

Whatever be the technique you use, regardless of the results, you will see that the observation in nature will give you much more information than a photograph. Besides, you will make stronger bonds with your models and the places where you’ve been. And maybe you will remember other fine details, even the ones to didn’t draw.

But before leaving home to the fields, try to draw this bird. It will be a fun!