Grupo do Risco – a group of Portuguese nature artists – took Wilder on its most recent naturalist expedition. We’ve found six secrets that eventually could save the artist that lives inside each one of us.

- Loose fear.

This is the last day of the expedition. For the past week, eleven nature sketchers have been drawing and painting the Sabor Valley, in the North of Portugal countryside. Standing or seating on the grass, they have been leaning over their sketchbooks, surrounded by pencils, brushes, pens and watercolours. They are called Grupo do Risco, a collective of artists created in 2007.

It’s 8am in the fire station in Torre de Moncorvo village. For the last couple of nights the group has been staying here, but before they’ve visited other villages: Macedo de Cavaleiros, Mogadouro and Alfândega da Fé.

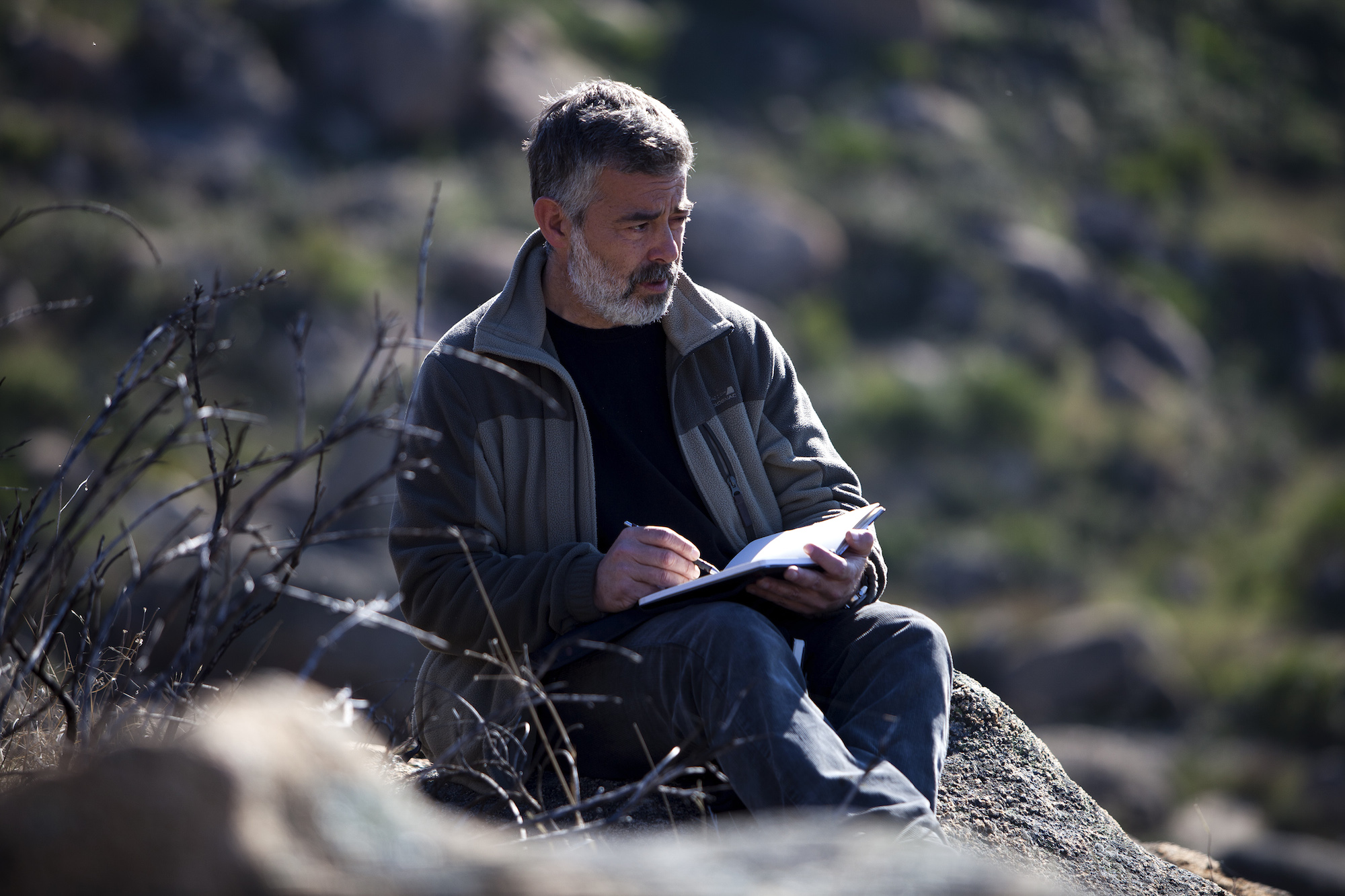

Inside the fire station’s café they order toasts, sandwiches and coffees. We take a seat at Pedro Salgado’s table. He is a scientific illustrator and the group coordinator. We ask him what we need to know and do in order to start drawing. “One of the most important thing is to loose fear and not to worry about the results”, says the artist, 54, grey hair and beard and a two tones grey polar jacket. “We need to break the myth that drawing is just for some, that it’s a gift. Drawing is for everyone”.

We think about these words for a while. When the eagle we’ve drawn looks like a chicken or the mushroom resembles a lettuce, is it worth to give it a try? “Some people say they can’t even draw a strait line. But our mind is more important than our hands”, he says.

Pedro Salgado is known to be the best Portuguese marine fishes scientific illustrator. Also, he is responsible for creating a new generation of scientific illustrators in Portugal and draws for more than 30 years. “Even I feel fear before starting a drawing. But after I start, that fear goes away”.

We are still thinking about this conversation as we enter the little bus that will take Grupo do Risco to several special places of the Sabor Valley. This group chose its name to honour the Casa do Risco, a XVII century school of Portuguese scientific illustration that existed in Ajuda Botanical Garden, in Lisbon. Three hundred years ago, the so called “riscadores” travelled the world to draw and paint the fauna and flora of the empire colonies. It was the golden age of Portuguese scientific illustration. Today, eleven of the 25 members of Grupo do Risco are in Trás-os-Montes region to draw and paint the landscape and nature that will disappear under the waters of a new dam.

- There are no such things as wrong drawings.

The bus climbs the hill and leaves the Sabor Valley quiet down there. From our window we see blackbirds and magpies passing by in a hurry. The sky is a blue bright.

At last the little bus stops at the top of the hill, overlooking the Sabor Valley.

Nádia Torres sets her portable chair and opens her black sketchbook on her knees. She chooses an angle and then starts drawing.

“It all starts when we unlearn how to draw”, says this artist, 52, living in Mértola, a village in the south of Portugal. “When we are little children, they tell us we must paint inside the lines, or that the Sun must always be yellow. And if we don’t do what we are told, then it isn’t right. That creates a deep feeling of frustration because it shows children what they can not do”.

When Nádia laughs, she bends back her head, as if her laughter had weight. She doesn’t seem frustrated at all, looking the landscape and looking back to the paper. “I always draw what I feel most difficult, because I want to be better at this. And I tell myself: ‘let’s see if I can do this’. Sometimes I don’t like my drawings, but that is part of the challenge”.

Susana Lemos, 40, is seating further ahead from Nádia. Wearing a grey wool bonnet and sunglasses, this artist from Lisbon has Lúcia Antunes on her left side and her watercolour box on her right side.

“Besides everything, we must accept that things not always go as we like.” And that doesn’t affect the passion she has for field sketching. “It’s a very important part of my life”, she says.

- Pick something you really like to draw.

In all the group’s expeditions – to Berlengas island, Douro Internacional, Ria Formosa, Amazon (Brazil), Madeira island, Doñana National Park (Spain) and Caramulo hills – it’s always the same procedure: when the artists arrive at a place in nature they take some time to observe and choose something they really would like to draw. There are ten minutes drawings or two hours drawings. It’s best that they don’t choose something boring.

This morning, Pedro Salgado has already chosen his spot and seats on a rock. He opens his sketchbook on his knees and places his black pencil case at his side. Then, he takes out the thickest pencil he brought. He’s going to draw the slope of the hill and the valley. When he starts the outline of the first stones and their forms and shadows he still hears the sound of a partridge in the distance. Soon after everything changes and the artist enters a world of silence, where nothing else exists but pencil and paper. It all fades away, the white and brown butterflies that dance at his feet near the grass, the group conversations nearby. The shepherdess with a stick on her hand, her three dogs and the sheep’s rattles passes right by him but it’s as if they had passed on the other side of the world.

Forty minutes later, Pedro Salgado returns to the slope of the hill. The landscape is already on the sketchbook pages. The work it’s done. For now.

4. Observe.

At 11:30am, the group is moving again, this time walking down the hill towards a place called Baldoeiro, next to the ruins of São Mamede church. There are purple lilies and yellow flowers scattered on the grass. And watercolour sets. Nádia, João, Delfim, Pedro Salgado, Marcos and Pedro Mendes work in concentration. Some are standing, others are seated, some with jackets on their heads for protection from the hot Sun.

João Catarino is seated on a stone, working on his watercolour. He removes the excess of water pressing gently a paper tissue against his ink blue sky.

At 48, João Catarino has no problem on admitting that he has an addiction: sketching. He is a member of Grupo do Risco since 2009 and he is a drawing teacher, a graphic designer and an illustrator.

“In our day-to-day life we are constantly running from place to place and we can’t stop. When you draw you are required to concentrate almost hypnotically”, he says. “The drawing grows like a tree, taking its time. We may see less things, but we see much more of one thing.”

This proper look, Pedro Salgado says, “is what makes you evolve from the phase when we draw just symbols of things to the phase when we draw really what we are seeing”. In that special way of relating with nature, “we realise details that otherwise we would overlook”.

- Draw a lot.

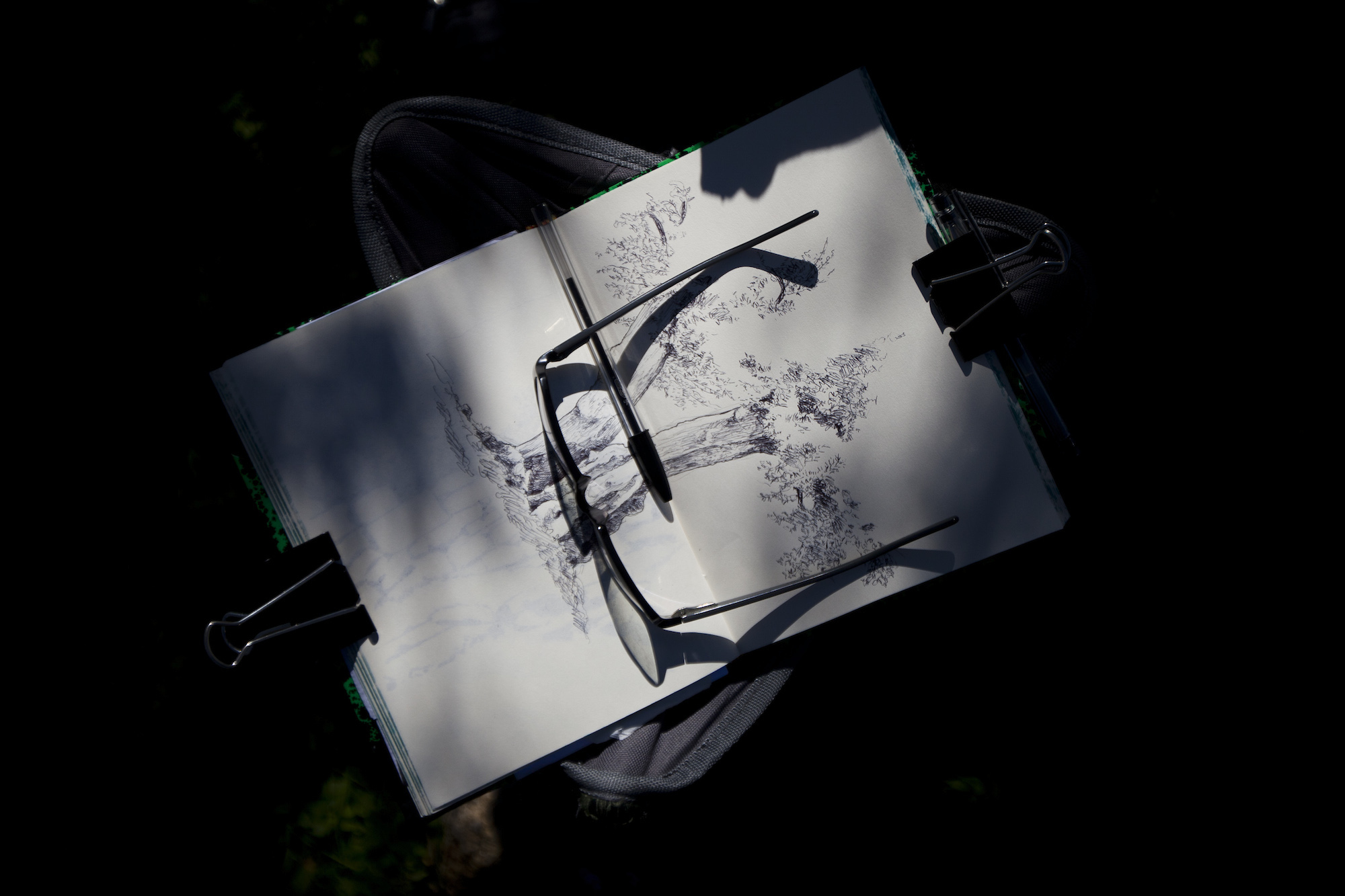

Cláudia Baeta, 44, illustrator and graphic designer, seats on the grass drawing a rock. Besides her, among pink and yellow flowers, is a brown case full of brushes and pencils. She works with two waterbrushes, one in her right hand and the other on her mouth; her left hand holds the watercolour set. Since she arrived at Sabor Valley she has drawn a lot. On the pages of her sketchbooks there are leafless ash trees, branches of almond trees, landscapes, a mill and ancient olive trees.

Lúcia Antunes, 29, illustrater and graphic designer, is right next to her, legs crossed to support her sketchbook. She draws the same rock with a black pen. Her pages are full of quick sketchs (because it started raining) and bigger paintings. She chooses the sketchbook she wants to use accordingly to the landscape or the time she has to work. But “sometimes I just pick the one at hand”, she says.

“The drawing depends on each one dedication”, explains Pedro Salgado. “It’s very important to draw every day. And without noticing, our hand feels more at-ease and free”.

- Peeking on the other’s sketchbooks.

At dinnertime in the restaurant everyone wants to see each other’s drawings. The sketchbooks are passed above the fruit salad, the coffees and the piles of plates with the leftovers.

“I can’t remember where this is…”, says Cláudia, looking at a landscape with a river in someone’s sketchbook. “Wait, I know this rock”, says Pedro Salgado, joyful. “I’ve drawn it too. It’s the eye of drawing doing its magic.”

“In this group no one hides drawings from anyone. When we draw its only natural for problems to arise. It is very important for us to be able to see how the other solved those same problems. We are always learning”, says Pedro Salgado.

And for us, from now on we’ll have always a sketchbook in our backpack.

[divider type=”thin”]

Now it’s your turn. If you would like to draw but you don’t know what, we suggest you take a look at Grupo do Risco works.