Dozens of young Iberian-lynx are being released in the wild in seven regions of the Iberian Peninsula to save this endangered species. Most of these animals were born in captivity, in one of the most ambitious conservation projects in Europe. A team from Wilder visited the only Portuguese breeding facility, in Silves (Algarve), and witnessed the birth of three cubs.

The calendar says today is March 28th, 2015. The gates of the Centro Nacional de Reprodução de Lince-ibérico (CNRLI, National Breeding Centre of Iberian-Lynx) are opened for us and we enter this conservationist compound. Since 2009 more than 70 lynx were born in these facilities (22 haven’t survived).

The sun shines and a gentle breeze plays with the yellow gorses and the white gum rockroses in this Algarve remote and quiet place. Nothing else moves. It’s as if the world stayed outside CNRLI gates.

Without realising it, we look for any sign of the lynx’s presence, one of the most rare species in Europe and in the world. Nothing. Not even a sound.

As we arrive at the CNRLI’s heart, the video-surveillance room, everything changes. Six computer screens show the animals in real time. These are images transmitted by the 21 cameras installed in the lynx’s enclosures, down the valley, hundreds of meters away from this room.

There are lynx in every computer screen, half hidden in the enclosure’s vegetation or in their dens, taking care of their cubs born a few days ago.

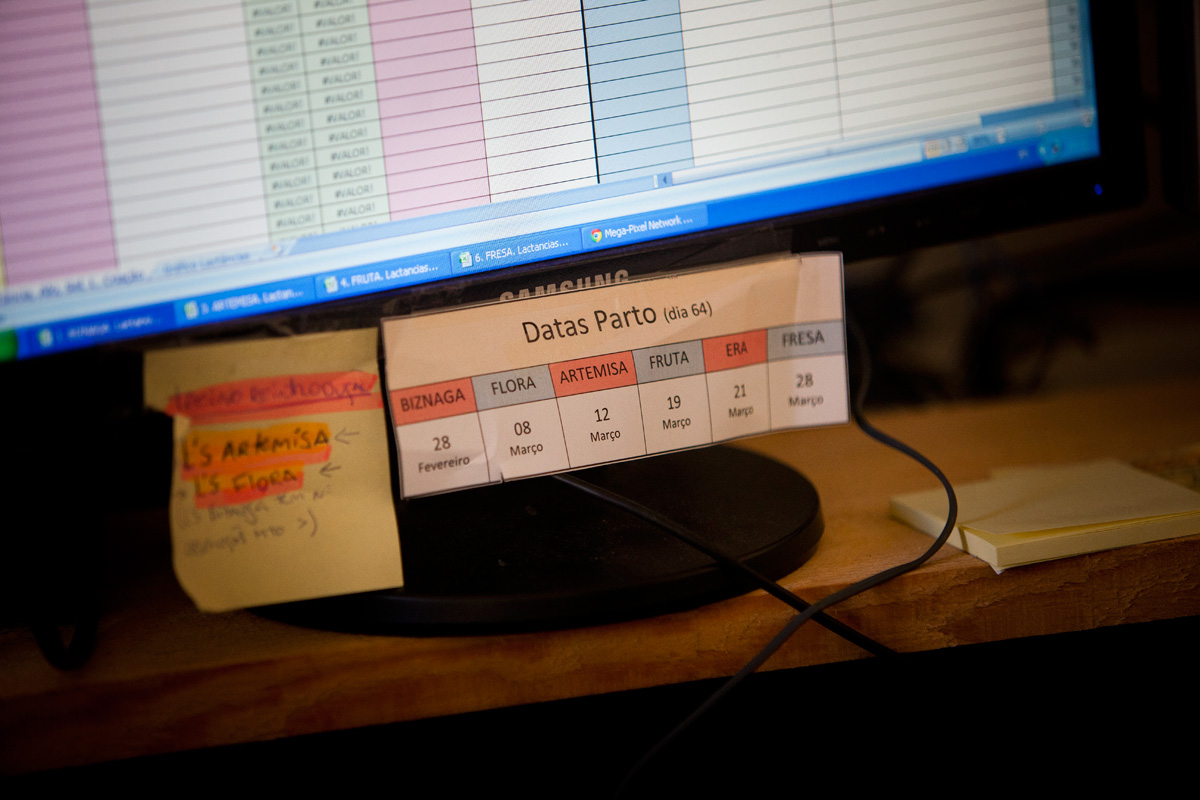

Fresa is the centre of all attentions. She is the last female to give birth this year. And everything’s ready for the big moment that could happen at any minute. Eight cubs were born in Silves this year so far.

The birth season is the result of a whole year of work for the 13 people and the volunteers that keep this centre up and running. The major goal is to have healthy cubs, training them for being free and, some months later, to release them in nature. This Iberian conservation project wants to help lynx return to the territories it once lived and from which it has vanished several decades ago. And all starts with moments such as these.

When a lynx is born it weights 180 grams. It fits the palm of one’s hand. The eyes are closed, the claws aren’t retractable yet and the impermeable fur will disappear within a week.

Nereida Sanchez Rico knows this all too well. She is one of the centre’s six keepers and has already witnessed several lynx births in this video-surveillance room.

The night has come and, at 10:15pm, here she is, waiting once more, with a cup of warm tea in her hands. There’s always a video-surveillance team of two and a keeper on duty. Nereida, 30, is finishing her shift with Sheila, Ivo and Miguel. All eyes are on the computer screens.

Fresa is in labor for a few hours now. She is inside her den in one of the 16 lynx enclosures in CNRLI. She dreams and trembles. Her breathing is heavy and fills the room.

This is a small room. It has a dark-blue sofa for three, five or six chairs and a long desk, full of computer screens.

The den where Fresa is since 8:20pm also seems small, with its 50 by 90 centimetres. Fresa is the biggest female in Silves, weighting 14 kilograms, and has already given birth to six cubs. “She is calm. She knows what she’s doing”, says Nereida, without taking her eyes away from the screen. She’s looking at a big close-up of Fresa’s head, with the tip of the ears shaped as paintbrushes.

Suddenly, Rodrigo Serra arrives and glances at the screens. “So, how’s she doing?”. Rodrigo, 40, is veterinary and the CNRLI director. We could bet no one in Portugal has ever held more lynx in his hands than Rodrigo. “She has non expulsive contractions”, answers Sheila, 24.

At 10:42pm, Fresa stretches herself and yawns. Sheila’s shift ends and is replaced by Miguel and Ivo. They are going to stay here until 7:00am.

Now the clock strikes midnight and Fresa doesn’t seem calm anymore. “She’s doing home improvements”, Rodrigo explains, as the lynx digs a shallow hole in the den made of cork, where the cubs will stay the minute they are born. Fresa cleans her fur knowingly. She’s getting ready.

This year, Biznaga and Fruta have given birth to three cubs each. Artemisa had one cub and Flora another. Era gave birth to two cubs that died minutes later.

Meanwhile, the day has dawned in this remote part of Algarve. Fresa is still in her den. Jan Valkenburg, a keeper, Verónica Madeira, member of the video-surveillance team, and Ana, a volunteer, are in the room watchful.

The time goes by and more people who work at CNRLI start to arrive. Some choose to stand leaning against the wall, others sit at the edge of the dark-blue sofa. It’s 1:15pm and a group decides to go grab something to eat in a nearby restaurant.

Lunch has hardly begun when Rodrigo’s phone rang. “The waters broke”. The hurry turns to haste. There’s no time to wait for the coffee to cool down so it is goes almost boiling down the throat. The bill will have to wait. “Welcome to our life”, says Rodrigo, winking. The car flies over the road, passing by the undaunted white and yellow wild flowers on the edge of the way.

At 1:50pm, the video-surveillance room is even more crowded. Telephone calls were made and the rest of the team who had the day off are here too. On birth days in CNRLI is always like this, we’re told. Jan is seated on the desk. Nereida, Verónica and Ana are taking notes. This is their shift and they are concentrated in what’s happening with Fresa. Behind them, Sheila, Rodrigo and Ivo occupy the little sofa, now with stacks of jackets, backpacks and notebooks. Miguel prefers to stand by the door, arms crossed.

Fresa is breathing heavily and turns several times in the den. “Come on, Fresa, sequences of five. That’s it”. Rodrigo counts the contractions and talks to Fresa.

And then, it happens. There’s one more Iberian-lynx in the world.

With its 180 grams, the cub rolls to the bottom of the den, in a furry confusion of tails and paws. The room is full with words of relieve and joy and smiles for another mission accomplished.

The hour of birth is registered at 2:17pm. But there’s no time for distractions. It’s crucial to confirm the cub is alright, to hear her and to observe her first movements. “Now, as usual, Fresa doesn’t show us anything”, says Rodrigo smiling. “Look, have you seen the head?”, asks Jan. A tiny feline head appears just for a few seconds between the mother’s paws. Fresa is licking her cub with all the care in the world. Soon after, the cub starts sucking, which is a good sign.

But, at 2:23pm, Fresa starts new contractions. Everything happens very fast and, at 2:44pm a second cub is born. “Bravo Fresa!”

And, just as in any football match we’re winning, we ask for just one more. Fresa accepts it and, at 3:12pm delivers her third cub. In the end, three cubs and 12 happy people, after having witnessed one of the rarest moments in the natural world: the birth of a species close to extinction.

This was a special day. In Silves were born three cubs, exactly ten years after the birth of the world’s first Iberian-lynx in captivity: Brezo, Brisa and Brezina. At March 28th, 2005, at El Acebuche (Doñana, Spain), Saliega gave birth to this three cubs. And in that moment a new path was opened to save the species from extinction. In those days, there were only 200 lynx left; today there are over 400.

Ten years after Saliega, Fresa continues to give this species hope.